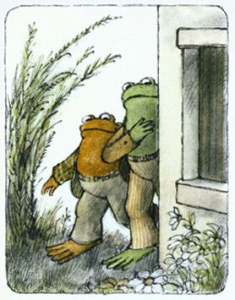

In one of my favorite Frog and Toad stories, Frog tells Toad how, as a young frog (or pollywog), he had gone to search for Spring. His father had told him: “Son, this is a cold, gray day, but Spring is just around the corner.” And so Frog had gone to search for that corner and for Spring. He turned several corners in his search: in the woods, a meadow, and along a stream, but he couldn’t find Spring. Finally, he got tired, and it started to rain. As he arrived back home, he saw another corner, the corner to his house, and when he went around that corner, there was Spring: the sun coming out, birds singing, his parents working in the garden, and flowers blooming. “You found it!” Toad calls, “You found Spring.” Turns out Spring was just around the corner, right there, where Frog had started, around a corner of his own house.

In one of my favorite Frog and Toad stories, Frog tells Toad how, as a young frog (or pollywog), he had gone to search for Spring. His father had told him: “Son, this is a cold, gray day, but Spring is just around the corner.” And so Frog had gone to search for that corner and for Spring. He turned several corners in his search: in the woods, a meadow, and along a stream, but he couldn’t find Spring. Finally, he got tired, and it started to rain. As he arrived back home, he saw another corner, the corner to his house, and when he went around that corner, there was Spring: the sun coming out, birds singing, his parents working in the garden, and flowers blooming. “You found it!” Toad calls, “You found Spring.” Turns out Spring was just around the corner, right there, where Frog had started, around a corner of his own house.

When I teach a meditation class, I often speak about the obstacles to mindfulness: dislike, desire, sleepiness, restlessness, and doubt; all of which have a common attribute: a wish for things to be different than they are. How often do we, in fact, wish for Spring when Winter reins (or rains, as my pun-loving boyfriend would point out) outside? Or perhaps we wish for more energy when we’re too tired to deal with the kids? How often do you doubt your choice of a route and wish you had taken another? Or that you were on the beach running instead of stuck at work? We think that if only our house was bigger (or smaller), our job better, our family more compliant, the government this way, and the world that way, then we would be happier, more satisfied, more at peace somehow. And yet most people agree that getting what we want is not the path to happiness. Research, in fact, points to other causes: developing gratitude, kindness, compassion, love and acceptance. And those, so I hear, are not around any corner outside in the world, but right here, inside us, living in a corner of our own soul.

Dharma teacher Ethan Nichtern writes: “Lacking the tools to get comfortable in our own skin and safe in our own mind, we get lost again and again in the existential transitions of life, blindly hoping that a true and permanent home lies around the corner, after just a bit more struggle to prove ourselves, a bit more time figuring out how to belong in our lives.” (The Road Home, 5). Searching for Spring around external corners may seem an innocent enough pursuit, perhaps even adventurous and exciting; but searching for ourselves, our true home, far outside of who we are, in other people’s opinions and reflections of us, needing to prove ourselves legitimate from the outside-in by someone else’s approval, and having our happiness depending on these external causes — is that how we want to live our life?

I admit it, though: I love corners. While hiking, I long to turn the next corner, go up the next hill or round the next tree or rock to see what’s there. I know, of course, that behind most hills are more hills, behind the next tree are more trees, and behind the rocky corner more trees and hills and flowers and lovely views, most likely not too different from those I already saw on the trail. And yet the attraction persists. I gaze soulfully at each trail that branches off the main trail and dream of following it. I plan to come back and visit yet another lake or climb another mountain, perhaps find more beautiful mariposa lilies which I can photograph in quest of the perfect lily photo. My desire to go on and on knows no bounds.

I admit it, though: I love corners. While hiking, I long to turn the next corner, go up the next hill or round the next tree or rock to see what’s there. I know, of course, that behind most hills are more hills, behind the next tree are more trees, and behind the rocky corner more trees and hills and flowers and lovely views, most likely not too different from those I already saw on the trail. And yet the attraction persists. I gaze soulfully at each trail that branches off the main trail and dream of following it. I plan to come back and visit yet another lake or climb another mountain, perhaps find more beautiful mariposa lilies which I can photograph in quest of the perfect lily photo. My desire to go on and on knows no bounds.

And yet, you might ask, in our latest hike on the Tahoe Rim Trail, what were my favorite parts?

A snack break by Fontanelles Lake, sitting on the rocks, watching the limpid color of the water, admiring the rivers of icy snow that still flow down the northern side of the hill, melting slowly into the lake.

Heart-stopping hues of orange, yellow and red in the meadow. Trees waving their branches in the breeze, some bare, some green. The sky a light blue that stretches on forever.

Sunset, colors deepening as the sun makes its way down through the clouds and below the mountains-behind-mountains-as-far-as-the-eye-can-see. The ground cold and hard, my breath catching as my mind conjures the image of a bear coming to attack me. Staying with it, sitting with it, trusting I am safe.

A rough-hewn picnic area by the river. Baby firs poking their heads up through the ground. The creek singing as it makes it way down little rapids that a woodrat could float on a woodratty raft. Tired. Hungry. Making our last breakfast on the trail and filtering pure water that will nourish my body’s cells. It is warm in the sun, cool in the shade, and I feel grateful for whoever made this beautiful camping and picnic spot, for whoever built this gift of a trail.

I love turning corners, but it’s this moment, the little moment, that counts. Sitting here, making room for myself within my own body, accepting that I belong here, now, in this chair, in front of this computer, with the sound of the boyfriend on the phone talking football to my son, a neighbor’s gardener blowing leaves outside, kids screaming in the pool down the road, the click of my fingers on the keyboard, and the alternating light and shade pattern of oaks shadows on yellow grass on the hillside outside. This is it: my legs falling asleep under the weight of the dog, my back warm, tiredness behind my eyes, ears pulsating with all this noise. This is what happiness is, inhabiting this moment, this little corner of joy.