“Breathing in, I know I am breathing in. Breathing out, I know I am breathing out.”

When first I came to live in California, the redwood forest seemed to me a dark, depressing place where few organisms lived. The tall, dark woods hid away the sunshine, and below all was muted, musty, moist. For a long while, I preferred the oak woodlands, the open spaces of Henry Coe State Park, where the horizon widens to include even the faraway Sierra Nevada’s snowy caps. Oaks and pines and the frequent sighting of wildlife in air and water and on land captured my imagination, providing me with a nostalgic connection to the Israeli landscape in which I had grown up.

“Breathing in, I am aware of my body. Breathing out, I am aware of my body.”

Over these past seventeen years — somehow, as though by magic — the redwood forest grew on me. I began to see it as a place of mystery and enchantment, holding its secrets close, so much of it existing far away from our human eyes. Up in the canopy, diversity thrives of mosses, lichen, trees, ferns, brush, and wildlife. Douglas firs have been known to grow on redwoods. Bay trees. Tanoaks. Berry-bearing brush, such as salal, huckleberry and gooseberry. Birds, like the marbled murrelet who only nests in the canopy of redwoods, Northern spotted owls, falcons and bald eagles. Salamanders, chipmunks, earthworms, crickets. But more than simply admiring the diversity of the forest, I learned to sense and love the trees themselves.

“Breathing in, I calm body and mind. Breathing out, I smile.”

Tall. So tall they touch the sky, dripping down a gentle rain of fog onto a ground feathery with duff. A lone banana slug meanders by, its slime pushing forest detritus down. I stand below a redwood and feel the strength of its roots in the ground. A redwood’s roots go only about a foot down, but they can stretch as far as a hundred feet away from the trunk. Kurt, my guide a few days ago at Big Basin State Park, tells me redwood roots of different trees fuse together to form one web. I close my eyes and imagine them communicating through the soil, holding onto-and-resting-in each other’s stretching arms, shooting up safe and tall to reach the sun. If their roots are entwined, are they one tree or many? Do the roots make the tree or do the number of trunks? And do they know, these trees, if a bay tree’s roots plunge into the earth through their web of life, that the bay is an “other,” and that they should not meld their roots with hers or a tanoak’s, or a pine’s?

“Dwelling in the present moment, I know this is the only moment.”

I chatter circles around Kurt as we walk. I can’t help it. Telling stories, asking questions, repeating information I had heard about redwoods, wanting to know more and more and more. Kurt seems patient, content. We visit the two tallest trees in the park. Funny enough, they are young ones who had sprouted farther up to the sky than older trees because of a spring seeping at their roots. The forest fills with the sounds of birds. Some we know: pileated woodpeckers laugh their mad laugh and drill into trees. Acorn woodpeckers waka waka out of sight, their methodical hammering lighter, less frantic. Jays caw and hop, and little juncos chirp. We see one banana slug, and then… I miss another and step on it. I am heartbroken, leaning down to find the slug writhing in redwood duff. A direct hit, Kurt says. How can such a magical day include such a devastating turn?

“Breathing in, I have arrived. Breathing out I am home.”

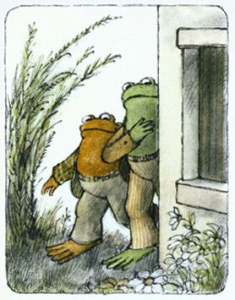

Three days later, I sit at the foot of a redwood tree at Wunderlich County Park. We are meditating to Thich Nhat Hanh phrases which I have adapted into a guided meditation. Across the creek, young redwoods grow close together on a hill which had been logged and logged again in the last one-hundred-and-sixty years, as had most of the land around us. But this lovely park is now protected and safe. The ground is cold, the air is colder, and dawn is but breaking over the top of the trees. Beside me, Anne-Marie and Adelaide are quiet. We are feeling the connection to the earth. Suddenly, crushing through the vegetation, someone approaches our peaceful spot. As the meditation wounds to a stop, we open our eyes to find a young deer tiptoeing down the hill, her eyes a deep brown in her honey head, stretched wide at the sight of the humans she had not noticed before. She sees us seeing her and hurries away. A pileated woodpecker madly laughs high above, and my heart is at peace. It’s time for our mindful walk.

“Breathing in, I know Mother Earth is in me. Breathing out, I belong.”

I go to nature to find connection, to remember that I am nought but a collection of bits and pieces of earth. The biblical God, anticipating science, had fashioned Adam out of dust, creating him from the very earth where he belongs. Whether walking or sitting, chattering away or so quiet that a deer misses seeing me nearby, I hold on to this sacred connection to all of life. Sometimes, I joke that being eaten by a mountain lion is the way to go, a way to ensure that I will not be embalmed and entombed or enshrined in a way that would prevent my returning to the earth. But in the coolness of morning, the redwoods permitting me to braid my human roots with theirs, death does not seem so bad, allowing me a glimpse of rejoining this land where every speck of soil is alive.

“Breath of Life” by poet Danna Faulds

I breathe in All That Is-

Awareness expanding

to take everything in,

as if my heart beats

the world into being.

From the unnamed vastness beneath the

mind, I breathe my way to wholeness and healing.

Inhalation. Exhalation.

Each Breath a “yes,”

and a letting go, a journey, and a coming home.