I always thought that El Capitan and Half Dome will long survive me. I took comfort in thinking that, even if us humans die off, the redwoods, most likely, will survive and continue to thrive, their trunks thickening and their canopy reaching high to a sky that will look more or less the way it does now. I believed some life will go on, even if it is different from what we know today, and some things, some features of this world we love so much, will linger on: perhaps the San Francisco Bay, or the Pacific Ocean, or Mount Rainier. The world will live on, in some shape or form. Life will go on.

Joanna Macy said to walk the razor-edge line between hope and despair. I try, but it is tough advice to follow, sometimes, when so much of what I hold dear is being threatened, and so few people around me seem to care. I care about people, but if it’s us or the world, it’s clear to me who is the one who needs to make way. As long as the world continues, I repeat as a mantra. As long as there’s El Capitan, or Mount Starr King, or Shasta, Mount Olympus, Rainier. In my attempt to hang onto any little bush on top of that razor-edge line, I forget that rocks and mountains, oceans and trees (no matter how long-lived they can be) are also subject to the rules of impermanence. Nothing stays the same. Not even the razor-edge line underfoot.

Joanna Macy said to walk the razor-edge line between hope and despair. I try, but it is tough advice to follow, sometimes, when so much of what I hold dear is being threatened, and so few people around me seem to care. I care about people, but if it’s us or the world, it’s clear to me who is the one who needs to make way. As long as the world continues, I repeat as a mantra. As long as there’s El Capitan, or Mount Starr King, or Shasta, Mount Olympus, Rainier. In my attempt to hang onto any little bush on top of that razor-edge line, I forget that rocks and mountains, oceans and trees (no matter how long-lived they can be) are also subject to the rules of impermanence. Nothing stays the same. Not even the razor-edge line underfoot.

An Israeli professor, I read in the newspaper, predicts that the earth will turn into Mars or Venus in 200 years (unless we follow the Paris agreement, he says). Edward O. Wilson, the famous myrmecologist, predicts that by 2050 50% of all the species in the world will be gone. I have read accounts that claim that 8 years from now the Central Valley in California will be so hot humans would no longer be able to live there. There’s other, similarly dire theories, but why repeat them all? Joanna Macy said not to believe any of these prophecies. She said to continue to do our work. To walk that razor-edge line. It’s not that we fight for as long as there’s hope, We fight for as long as there’s a cause for which to fight. As long as there are pandas, hummingbirds, ants. As long as there’s Bears Ears. As long as the Colorado River still runs.

A year ago, a young friend was diagnosed with cancer. He began treatment, encountering set-backs one after another, but not losing hope. At least not for long, at least not for a while. A few weeks ago, his mother let us know that he was now in hospice care. To me, heart sinking, heaviness in the chest, contraction all over the body, brain shouting no, it meant that life is almost gone. But it turns out my understanding was inaccurate. Hospice care means living as well as possible and with compassionate care the life we have left. Instead of planning for a faraway future, it means living this moment fully. It doesn’t mean we stop treatment or lose hope. It means opening up to the love — and the life — that’s here.

A year ago, a young friend was diagnosed with cancer. He began treatment, encountering set-backs one after another, but not losing hope. At least not for long, at least not for a while. A few weeks ago, his mother let us know that he was now in hospice care. To me, heart sinking, heaviness in the chest, contraction all over the body, brain shouting no, it meant that life is almost gone. But it turns out my understanding was inaccurate. Hospice care means living as well as possible and with compassionate care the life we have left. Instead of planning for a faraway future, it means living this moment fully. It doesn’t mean we stop treatment or lose hope. It means opening up to the love — and the life — that’s here.

Joanna Macy said to walk the razor-edge line, but I can’t. I teeter-totter between hope and despair, between sadness and joy, between anger and acceptance. Only one constant stays: I love this world. I love the hummingbirds which come buzzing around my flowering abutilon plant. I love the deer and the rabbits who eat the plants which I plant for them in my garden. I love the flowers cascading down a madrone and the spritz of perfume that accompanies the flowery bouquets of the buckeye. I love this beautiful light blue sky and all the weather that comes with it. I love the sticky sand on the beach, the breaking waves, and the gorgeous pod of dolphins which rode them today to the horizon. My heart, little, fluttering, fearful, opens up to touch these miracles, to hug them, to bear witness that they are here. And I think to myself: we all live with impermanence. We all, the world included (and whether we realize it or not), have the life-limiting condition which is life itself.

A mother, diagnosed with lung cancer, wrote about the irony if she died of a car accident instead of her cancer. I think to myself: our young friend may be sick. He may not live to be 80. But neither might I. We none of us know the day of our death, and neither does the earth. In some ways, we all ought to live with the compassion and love of hospice care, bearing witness to our time here in this life and to the life all around us — to the beauty which surrounds us, the miracle of life which is here. Opening up to the fragility of this world.

A mother, diagnosed with lung cancer, wrote about the irony if she died of a car accident instead of her cancer. I think to myself: our young friend may be sick. He may not live to be 80. But neither might I. We none of us know the day of our death, and neither does the earth. In some ways, we all ought to live with the compassion and love of hospice care, bearing witness to our time here in this life and to the life all around us — to the beauty which surrounds us, the miracle of life which is here. Opening up to the fragility of this world.

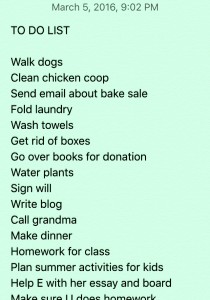

My partner said last night: I am sure life exists on other planets. It might, I wanted to say, and it might not. Instead of turning our thoughts once again outwards, why not focus on what is here right under our noses, under our feet, beneath our hands, and to this earthy air breathing in and our of our lungs. This touch, this smell, this sound. This beautiful earth whose day of death may be near or far. We don’t know. We walk the razor-edge line. We fall into despair, and we desperately hope. We sign petitions. We go to vote. We write a blog. And maybe one of these treatments will work, and the earth and its creatures and all the life on it will live on for another day. Maybe the cancer that we have inflicted upon the earth will heal, and maybe it won’t. For now, there is life. That’s all I know for sure. There is this flower and this bit of ground, this humid air, this birdsong, this crush of a wave on the beach, and the laugh of a human child as she runs from the wave along the shore.