This fall, I took an Intro to Park Management class at a local community college, thinking that I might get back to my youthful dream of becoming a ranger. Already in the first meeting, I knew I was in the right place. The class was not only fascinating, but inspiring as well. I got the impression that no matter their age, the teacher believed in each student’s ability to find work in public land management.

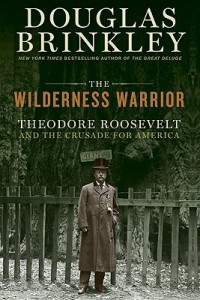

The class introduced me to an entire world of history, politics, literature and art that has to do with our public lands. I was fascinated, scribbling down each book recommendation the teacher mentioned and then reading them one by one. My favorite, so far, is Wilderness Warrior by Douglas Brinkley, an environmental biography of Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt was an avid hunter and naturalist, a champion of land-and-wildlife preservation and conservation. During his presidency, he set aside nearly 230 million acres under federal protection in 150 national forests, the first 51 federal bird reserves, 5 national parks, the first 18 national monuments, and the first 4 national game preserves. In 60 years of life, Roosevelt was active not only on the conservation front. He was a prolific author, a dedicated letter writer (who wrote an estimated 150 thousand letters), social activist, military leader, adventurous explorer, rancher, nobel peace prize winner, and more.

Roosevelt believed in something he termed “the strenuous life.” Articulating on this concept in an address he gave in Chicago in 1899, he said: “I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife; to preach that highest form of success which comes, not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph.”

Roosevelt, it seems to me, certainly lived the life he preached.

The strenuous life, I confess, is also the life I had always wanted to live. Roosevelt described it: “…the higher life, the life of aspiration, of toil and risk….” Roosevelt’s address, intended to raise public support for war in the Philippines, would have stirred the 18-year-old me to the core. I too believed in public service to one’s country. I did not yet think of war as something to be avoided, but as an opportunity for glory, heroism, and self sacrifice. I longed to live the strenuous life, to prove myself worthy. As Roosevelt said in his speech: “We do not admire the man of timid peace. We admire the man who embodies victorious effort.” I, too, wished to be that man… or, er, that woman.

Some historians believe now that Roosevelt’s energy came from having had bipolar disorder — without ever suffering from the depression side. To me, whether Roosevelt’s energy was due to a mental disorder may or may not be an important point. I recognize in Roosevelt’s philosophy the highest ideal which I have placed before my eyes throughout my life. Knowing that this philosophy may be what we could call insane is a moot point. Most of our beliefs, after all, tend to seem illogical, unreasonable, even crazy to other people, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy to stop believing in them. As a society both Israelis and Americans seem to live a life of yearning for this principle, that work will save us, that work is the highest ideal of all.

I have lately developed the belief that a lot of my suffering is caused by putting work, or the strenuous life, if you will, up on a pedestal. The other day, my therapist said that rather than try to let go of always pushing myself to be doing more (and thinking I was never enough), I needed to accept the part who always pushes me to be doing more. Perhaps for affection’s sake, I should name that part Teddy, to remind myself that it is just a part, not all of me, who wants to live this strenuous life. And it is not all of me. There are parts of me who long for peace and ease, for acceptance of things as they are. There are parts of me who are overwhelmed by this constant pushing for more and are feeling mowed over and need a break from all this doing in order to figure out what, if anything, wants to be done.

Practicing life in the face of “A Year to Live,” I find myself less willing to rush and more interested in savoring. I find myself wanting to cherish moments rather than chase through them. I begin to understand that living this year as though it is my last is not about doing more, or doing at all. As a beginning, at least, it is about understanding that nothing needs to be changed, and that my life is right and whole just as it is. In a way, the bucket list can wait for after my death. For now, I’m just going to live as though I am, in fact, going to live today.

To read Theodore Roosevelt’s 1899 speech given in Chicago, click here, “The Strenuous Life”

A lot of the information in this article came from this page in the Theodore Roosevelt Association website.

Some interesting discussion of the possibility TR was bipolar can be found in this article.