All my life, books transported me far away to worlds I could hardly imagine in my everyday life. Rapturously, I followed Tarzan’s adventures in the jungle, Robin Hood’s exploits in Sherwood Forest, Michael Strogoff’s journey through Siberia and Ivanhoe’s struggle to return justice to England at the time of the crusades. I adored these heroes. I wanted to emulate them. I wished to be a hero myself.

Thirty years ago, few female characters existed in literature that raised in me similar desires for grand action and bravery. And yet, though a girl (and now a woman) myself, I yearned to read about –and to live — a life of heroic deeds. When I enlisted in the Israeli army in 1990, I hoped for a chance to be a warrior. Instead, I found myself serving in the army as more or less a secretary to a bored (and fat) older man who smoked too much and thought my main job ought to be serving him coffee and removing the cup after he was done.

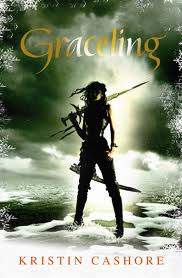

Girls readers today have more female literary role models, heroines who fight for justice, peace, and freedom, than I had growing up. Whether it is Katniss in The Hunger Games, Katsa of Graceling, Beatrice in Divergent, or Celaena of Throne of Glass, teen literature overflows with female characters who are survivors. They are physically and mentally strong and capable of defending themselves even under the most extreme circumstances. Girls today need no longer dream of being a hero: they can become a heroine.

I recently read an article by Sarah Blackwood which discusses the character of Bella from the popular Twilight Saga. Blackwood describes Bella thus: “Bella waits, she wallows, she thinks, and feels, and worries, and wonders. She does not actualize in the sense we have come to expect from our heroines….” Blackwood mentions Katniss and Katsa as contrasts to Bella, yet she wonders: do these strong, actualized and empowered girl characters in fact represent a male perspective on what it means to be actualized and empowered? Have we feminists fallen into a new trap where, in an attempt to carve our equal status in the world, we define our strength by male guidelines? Have we rejected the passive, gentle, forgiving woman — the traditional definition of the feminine — to become nothing more than a tiny man?

While I would not like to reject out of hand any of my feminine qualities (forgiveness and gentleness especially seem to me worthwhile to keep), and while I appreciate Bella’s popularity among teen girls — clearly her character answers a need in them — still I personally have always turned to the chivalrous, heroic and brave rather than to the passive or needy. In truth, none of the Twilight characters particularly appealed to me, male or female. Instead, I turn to Katsa whose ability to survive, her prowess in fight, and her sense of justice are ideals I wish to live by, or Eugenides, from Megan Whalen Turner’s The Thief, whose daring, wisdom, and loving heart made me his fan for life. My wish to be like either of them depends less on their gender and more on their qualities. And similarly, it is not either gender that I crave, but their courageous, loyal heart.

To read more:

The article about Twilight’s Bella.

My review of The Thief.

My review of Graceling.

Comments are closed.